“The law, in its majestic equality, forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal their bread.” Anatole France, The Red Lily (1894)

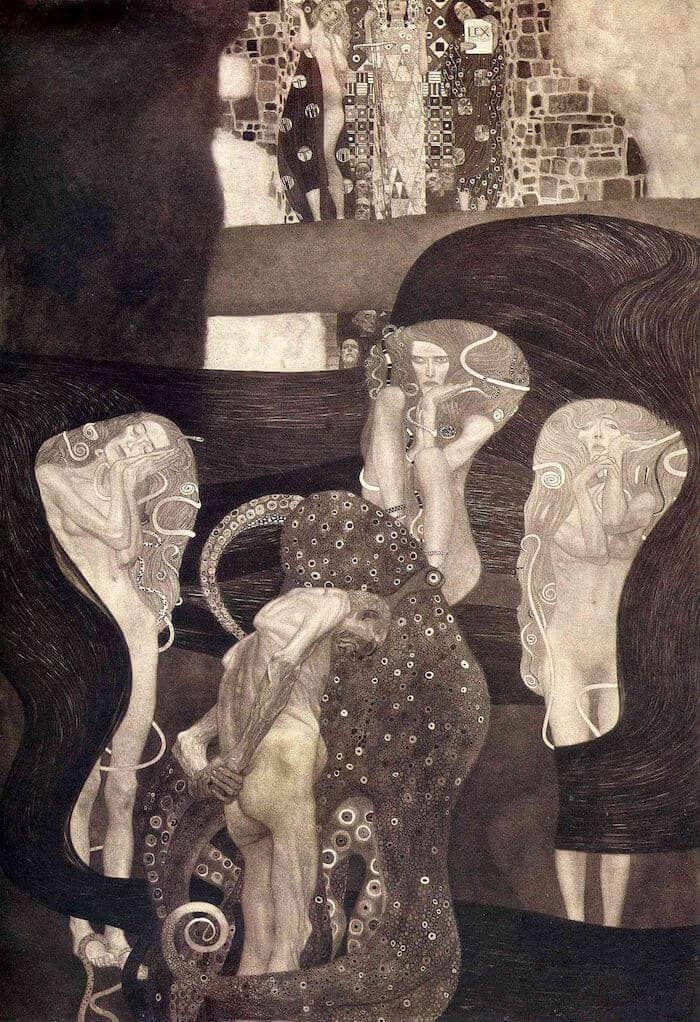

‘Jurisprudence’ by Gustav Klimt, 1903

After a frantic bureaucracy of visa and immigration, Vienna’s silence and peace feel less like a relief and more like a void. I have been staying here since September and have been walking past the ghost of Kafka and Mozart, and occasionally missing home. But surprisingly, it was not the warmth of the home that I had missed; it was rather the lack of adrenaline of uncertainty that had been providing me with an existential boredom. Suddenly, in one of my philosophy of law classes, I came across Gustav Klimt’s ‘Jurisprudence’ and the boredom was replaced by a grotesque portrayal of justice where an old man was being crushed by the Furies and the Gods were looking on from above with stoic indifference. I felt quite calm and soothing because of the terrifying sense of comfort, a dopamine of horror perhaps, if I can call that. It was very similar to the chaos that I had left behind sometime earlier. After a good night’s sleep, I felt a bit ‘itch’ being a sadist in the morning, but that feeling was not for long as I came across a darker reality in the newspapers, a man in Bhaluka, Dipu Chandra Das, hanging from a tree, being beaten and burned by a ghostly crowd which seemed a literal manifestation of Klimt’s nightmare in my own homeland.

In Klimt’s canvas, there is a victim who is no longer fighting the tentacles of the Law. He is lost, surrendered to it. The old man is not being punished by the Law, if one looks closely, he is being consumed by the lack of protection of the law. It might also be said that the Law had occupied or entangled the body in such a way that he can neither move nor shield himself from the horrifying pain. Meanwhile, the three goddesses, Truth, Justice, and Philosophy, exist on a very different layer of the story, watching with sheer indifference. They are allowing the incident to happen, committing a grave act by actively omitting their power to protect it.

The December night for Dipu Chandra Das was somewhat very similar to the painting. The mob or crowd dragged him through the streets, circled him, and hanged him from a tree. And this did not happen in an isolated place, but in a public street, where hundreds of people gathered, did ‘live’ on social media, beating him to death, and burning him till the body turned into ashes. Klimt’s Jurisprudence was too dark for the University of Vienna in 1903, but it happened in Bangladesh, in Bhaluka, in 2025 or should I ask, was it just Dipu or Bhaluka, or was it the entire socio-political structure that had orchestrated the nightmare?

In elementary jurisprudence in law schools, we are taught about Thomas Hobbes’s state of nature and social contract, a bridge between cynical, fear-driven human clans and the state where the people surrendered their rights to the state as a gateway out of eternal chaos. This agreement, the very foundation of legislation, stands as an architectural blueprint for society. But, in the moments of institutional collapse, in the moment when Pandora’s box flung open, the people rushed to reclaim the power that they once had surrendered to the state. They transformed into the tentacles to entangle the weak, marginalized minorities, persons who are standing on a lower footing due to their identity. A people-pleasing state, despite its promise to protect everyone equally, reduces itself to a biased entity towards particular identities and fuels the brain of the predator octopus. And the civil society, at the point of intellectual bankruptcy, becomes cheerleaders of the state or the specific crowd that the state seeks to please, and stops becoming a watchdog against the power. Just like the Furies in the canvas, civil society is manufacturing a legitimacy of the state and the primal psychology of the crowd. In Bhaluka, the fire was lit by the hands of hundreds of people, but the fuel was provided by the power structure that thrived on this very chaos.

The horror reaches its apex when a fragile, post-conflict state does not merely tolerate the ‘tentacles’ of the mob but actively protects it. The state, out of a desperation to look powerful, rebrands the violence as a democratic will and allows the crowd to be its proxy executioner. The ‘stoic indifference’ that one will inevitably find from the Goddesses in Klimt’s canvas is, in reality, a calculated silence. In Bhaluka, the mob was the law’s shadow while performing the execution that a ‘modern’ state could not legally claim, yet needed to prolong its fragile grip on power.

The social contract that we celebrate in Academia, in many ways, is merely upholding a ghost. We believe that the state will protect us all equally, yet the reality remains that ‘some are more equal than others’. The revolutions and the upheavals often lead to a tragic irony, where they descend to the tyranny that they once intended to overthrow, echoing Orwell’s Animal Farm. Faces of the power change, but the victims remain the same; marginalised, workers, ‘others’. Dipu Chandra was not failed by a mob; he was excluded by a contract that never meant to protect him, a minority whose life had no currency in the corridors of civil society and the state.

Here, my window leads me to a cold, snowy world, but in the reflection in the glass, when I can see myself, I go back and find myself belonging to the place where the law is not a shield, just a rotating sword, constantly changing hands, executing the powerless, marginalised, in a never-ending cycle. Bhaluka was one chapter of that grim history. The snow falls, but the cycle burns on.

A silent, snowy Vienna afternoon, 2025

Reference:

France A, The Red Lily (Winifred Stephens tr, Stephane Leduc 1910)

Klimt G, Jurisprudence (1903-1907) [Painting, Ceiling of the Great Hall, University of Vienna; destroyed 1945]

Natter TG, Gustav Klimt: The Complete Paintings (Taschen 2012)

Orwell G, Animal Farm (Secker and Warburg 1945)

‘Garment worker beaten to death in Mymensingh? What happened that day?’ Prothom Alo,

https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/crime-and-law/b0lqem1owr